Note: This is a detailed run-down on Uranium’s history and how it got to where it is now. The aim of this article is to inform our readers about the potential in Uranium. We’ll be doing an entire detailed analysis on spot Uranium, Uranium Miner ETFs, and individual Uranium names next.

Uranium has likely reached a key inflection point that could accelerate the price over 3x higher this decade. Uranium has slipped into a consistent widening deficit, resulting in an incoming supply shock. But how did we get to this point?

From the start of the nuclear age in 1945 until today, the uranium industry has gone through 4 distinct periods. Each period has been unique in terms of supply and demand, leading to significant price swings. The market has now entered its 5th major period, likely defined by persistent supply deficits.

Period 1: 1945-1969

The 1st period occurred from mid-1940s to the late 1960s. Governmental stockpiling, primarily for weapons and nuclear power advancement, drove demand. After the Trinity test in Los Alamos (world’s first nuclear explosion) and the subsequent bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, attention quickly turned to nuclear’s commercial applications.

The Soviet Union (USSR) and England inaugurated the first 2 nuclear power stations in 1954 and 1956, with England’s being the first truly commercial reactor. Despite these early reactors, commercial demand remained extremely low. Protection of supply remained an important factor of national security after the war as the US and Soviet Union built up their atomic arsenals.

Between 1945 and 1969, Nuclear Engineering International estimates global uranium supply totaled 900 mm lbs of U3O8. Roughly half of this material was purchased by the US Atomic Energy Commission (AEC), while 40 mm lbs was purchased by the nascent commercial nuclear energy industry. The remaining quantity was officially unaccounted for, but it likely made its way to a combination of US, British, French, and Soviet Union’s government stockpiles.

Period 2: 1970-1983

The uranium market began to change as commercial nuclear power gained adoption. Private sector utility buying became a major source of demand. Total installed capacity grew from 1 GWe in 1960 to 10 GWe by 1970 and 100 GWe by 1980. This arrival of the nuclear age also led to a speculative boom in uranium mining. Despite the widespread adoption of nuclear power, mine supply grew faster than reactor demand throughout the decade.

The 1970s were a period of rolling energy crises and insecurity. As a result, commercial buyers were more than happy to build up excess uranium inventories. From 1970 to 1983, mine supply exceeded reactor demand by 450 mm lbs of U3O8, all of which ended up in commercial inventories.

Adding to the glut, the AEC reclassified approximately 100 mm lbs of its stockpiles from “governmental” to “commercial,” making it available to the nuclear power industry. By 1983, commercial inventories were around 550 mm lbs, a quantity that was enough to cover reactor demand for almost 8 years. As a result, prices had already peaked by 1983 at nearly $40 per pound and started a multi-decade decline.

Period 3: 1983-2010

Uranium mine supply peaked in 1982 and fell modestly in the coming decade. Meanwhile, reactor demand grew robustly and finally exceeded mine supply in 1991. The deficit persisted until the Fukushima incident in 2011. However, secondary sources of uranium helped fill the supply shortage.

In 1993, Russia and the US agreed on the “Megatons for Megawatts” program, through which Russia pledged to decommission 20,000 nuclear warheads and convert the highly enriched uranium into 15,000 tonnes of low-enriched uranium, which was suitable for manufacturing into reactor fuel. Fuel recycling became widespread in the UK and France during this period as well, as did enrichment-tailing reprocessing. Commercial inventory destocking contributed additional supply. All this secondary supply put downward pressure on uranium. Prices finally bottomed around $7.10 per pound in 2000.

By the mid-2000s, commercial inventories had fallen drastically. The Russian disarmament program was due to expire in 2013, threatening to reduce secondary supplies materially. By 2005, uranium price tripled from $7 to $21 per pound. By the late 2000s, commercial inventories had fallen nearly 70% and stood at only 200 mm lbs. Commercial inventory coverage went from 8 years in 1983 to less than 2 years by 2007. Utility buyers scrambled and speculators jumped in.

Spot prices reached a high of $136 per pound in June 2007, with long-term contracts settling at $95 per pound: an increase of between 12x to 18x in just 7 years. Uranium collapsed during the 2008 Financial Crisis but resumed its rally in 2010. By January 2011, uranium was once again over $60 per pound and commercial inventories were at a mere 150 mm lbs.

Period 4: 2011-2020

On 11th March 2011, the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami led to disturbance in Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi reactor leading to a nuclear accident. Subsequently, Japan shut down all its nuclear reactors over the next several years. European demand, led by German decommissioning, fell by 25%. As a result, global reactor demand fell sharply between 2010 and 2012 before beginning a slow recovery. Meanwhile, responding to the prior uranium boom, primary supply grew for the first time in decades. Production in Kazakhstan grew by nearly 50% between 2010 and 2016. Primary production nearly satisfied reactor demand in 2015 – a first in over 25 years.

Secondary supplies weighed on the market as well. Although the Russian disarmament program ended in 2013, tailings re-enrichment, recycling and underfeeding continued to contribute a significant amount of U3O8-equivalent by 2016. Between 2011 and 2018, the uranium market was in surplus by 265 mm lbs., all of which ended up in commercial inventories. Commercial stockpiles, which started the period at a record-low 150 mm lbs., reached 415 mm lbs. by 2018, covering reactor demand for 3 years. The uranium price meanwhile remained depressed, averaging less than $25 per pound between 2016 and 2020.

Period 5: 2021-Present

Uranium’s structural deficit has accelerated dramatically since 2021. After spending a decade decommissioning its nuclear reactors, Europe and the US appear to have finally reversed course. Wind and solar sources simply cannot provide efficient base-load carbon-free electricity. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 put Europe’s natural gas supply at risk, bringing renewables’ shortcomings to the fore.

A new source of demand burst onto the scene in 2021 as well: the financial buyer. Led by the Sprott Physical Uranium Trust, financial vehicles have acquired between 25 and 30 mm lbs each year in 2021 and 2022. Unlike open-ended funds such as $GLD, the financial uranium vehicles are closed-ended, meaning the material cannot readily flow back into the commercial market. Once material is purchased it’s permanently locked up.

As a result, the uranium market experienced a deficit of nearly 180 mm lbs between 2020 and 2023. The deficit has been met by the commercial inventories that had accumulated following Fukushima. By the end of 2023, commercial inventories should be back to 250 mm lbs, covering reactor demand by less than 18 months. The last time commercial inventories reached these levels in the mid-2000s, prices spiked to their all-time highs of $136 per pound. We expect a similar path this time around.

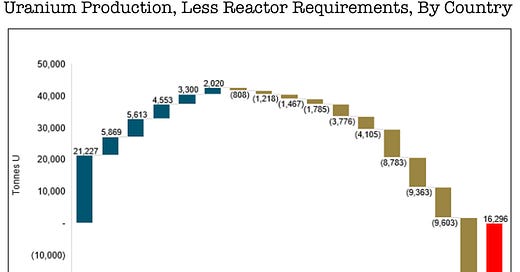

Looking to the end of the decade, global uranium markets are set to tighten to unprecedented levels. Looking only at nuclear power plants that are currently under construction, reactor demand is set to grow from 188 to 240 mm lbs by 2030. If every uranium-producing country gets back to its maximum output (a big IF), primary production will only grow from 140 to 174 mm pounds by 2030.

Assuming secondary supply stays flat at 20 mm lbs per year, the annual uranium market deficit will grow from 27 to 45 mm lbs by the end of this decade, before factoring in further financial buying. The cumulative deficit between 2023 and 2030 will likely exceed 250 mm lbs, completely depleting all commercial stockpiles. Furthermore, financial accumulation is likely to accelerate once speculators realize the small size of the market and the demand-supply dynamics.

Utilities remain dramatically under-contracted post-2025. Fuel buyers have been very complacent in recent years, due to the persistent commercial inventory overhang following Fukushima. Simply put, it has paid to wait to secure supplies. That dynamic is quickly changing as fuel buyers feel insecure and under-covered for the first time in over 15 years. Although it is an opaque market, all signs point to uranium entering into a secular bull market this decade.

Disclaimer - All materials, information, and ideas from Cycles Edge are for educational purposes only and should not be considered Financial Advice. This blog may document actions done by the owners/writers of this blog, thus it should be assumed that positions are likely taken. If this is an issue, please discontinue reading. Cycles Edge takes no responsibility for possible losses, as markets can be volatile and unpredictable, leading to constantly changing opinions or forecasts.

Nice history piece!

so, how do we trade this information please?